Some of you may be aware that I am following John Michael Greer’s series of blog posts about Wagner’s Ring Cycle.

His focus is the philosophical and historical underpinnings of the magnum opus of one of the greatest composers of western music.

That is good. Please read the posts at www.ecosophia.net. Now that we have these resources available for free, there is no reason not to educate oneself about the core works of world art.

I will throw in my two cents from time to time, to sort of flesh out the story.

Das Rheingold opens with three river fairies, the Rhine Maidens, singing about their father’s gold that lies hidden at the bottom of the river. A dwarf approaches, attempts to get fresh with the pretty girls, and, when he is rebuffed, steals the gold.

Like a lot of fairy tales, there is some element of actual scientific and folkloric truth to the story.

First of all, why is there a pile of gold in the river being guarded by these three sister spirits?

Rivers were and remain frequent methods of travel, particularly in trade. Precious metals were used as money and would be aboard these ships, often in copious amounts. Ships occasionally sink, their contents going with them. Thus there would be a significant number of shipwrecked boats lying on the floors of rivers, with chests full of money and, for some time, the skeletons of the hapless traders, especially in cooler waters. Even today, we are still finding the legendary treasure troves from ships that went down thousands of years ago.

Hence the spirits said to be guarding gold in the Rhine would, in popular imagination, not be far from the truth, only they would not be lissome maidens but gnarly dudes.

In medieval Scandinavia prior to the Christian Era, the type of currency most commonly used was not gold but the silver coins brought in by Islamic traders. There were giant piles of this currency in these countries. People used to bury it in the back yard for safekeeping. Sometimes they evidently forgot where it was, or died while concealing it, such that even today ordinary people with metal detectors occasionally unearth hordes of silver coins of Islamic stamp in their back yards or farm fields.

In pre-Christian times, kings or other very wealthy people were buried in burning ships along with piles of treasure and household items, as well as slain wives and slaves, who went with them for the journey. The Prose Edda contains a reference to such a burial in the tale of the death of Baldr, as does the historical memoir of Ahmad Ibn Fadlan.

King’s Burial & The 13th Warrior

Thus the idea of buried or lost treasure has an element of truth in it.

Ships from even further back in history, would have more access to gold, so the idea of gold is not entirely far-fetched. Archaeological finds in England have yielded such treasures.

However, for the sake of a good tale, it is not a bad idea to pep things up a bit. Let’s say the silver was gold, and the departed traders — Vikings — were elegant maidens.

Treasure hunters abound, and no doubt when a rich vessel went down, the people in the area would try to dive for the treasure, often drowning in the attempt.

Every body of water has areas of particular danger where currents, soft muddy bottoms, or trees and branches passing by have proven particularly deadly.

There is a type of spirit in Germanic mythology called a “Nixie” that is a water sprite that lures swimmers to their deaths.

Certain locales in Scandinavian rivers were warned against, either as natural phenomena, periodic flooding, sandbars deadly to vessels, or just a repetitive motion in regional folklore of people drowning. Part of the witchcraft is to make an offering to these spirits and ask for a favor, but be careful not to go into the water, or you might be carried away by the spirit, sometimes in the form of a horse.

Modern excavations have, in fact, unearthed signs of extensive activity in the Bronze Age layers of sediments, such that offerings were evidently made, or people drowned there a lot, or there was human sacrifice — perhaps all.

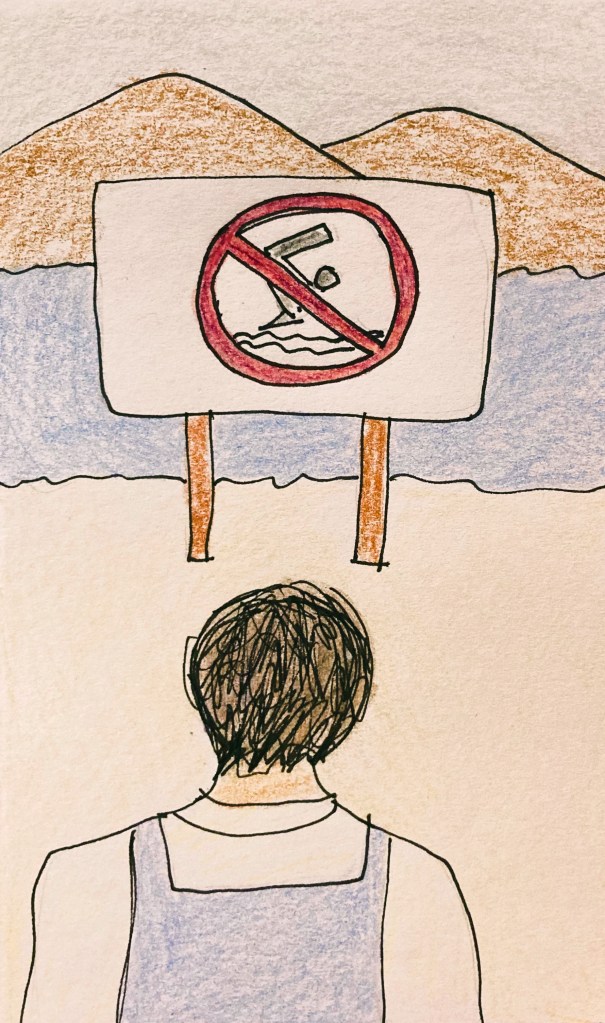

My grandparents used to live near Barstow, California. There is a river that flows alongside the highway, and at certain places there are signs that say, “Do not swim here. Two hundred lives lost.”

There are dams upriver, and when the sluice is opened, the water gushes out and raises the level of the river by ten feet or so, and the onslaught of this water is simply more than a normal swimmer can survive.

I used to drive this road about once a year getting to and from the airport in Los Angeles, and was amazed to see the signs change by the year.

Do not swim here — 200 lives lost.

Do not swim here — 215 lives lost.

Do not swim here — 225 lives lost.

Yet fools go into the water every year, and every year the sign changes.

To have such a sign — or local knowledge constituting a sign — is to dare the feckless to beat the odds. Let’s say one is driving along, or even walking along, for this is an area frequented by agricultural workers. The sun is beating down mercilessly in the desert, and there is a lush and fairly clean spring, running right by the road where one is walking. Who would not be tempted to go down there, take off your shoes — or more — and get cooled off before continuing the journey? Suddenly you hear a rumbling, look up, and a wall of water is bearing down on you. There often isn’t time to make it, not just to the shore, but all the way up the bank.

The sign changes: 226 lives lost.

In the end, that sign is as much a fatal fascination as a warning to those who pass it, and that crook in the river comes to be spooky in the minds of the locals, perhaps causing the imagery of ghosts or malignant echoes of past lives lost, at least in the imagination — or more.

Another case in point, when I was a teen, I was told that the MAR-MON missionaries were not allowed to swim, even in pools. It was explained to me that there are demonic powers in water that often take the lives of these young men, even when they are accomplished swimmers and in otherwise peaceful waters.

Third, when I was in college in Provo, Utah, one winter a man went out ice fishing on Utah Lake, fell in, and drowned. For some reason, the State opted not to drag the iced-over lake, send out ice divers, or do anything to recover the body, reasoning that, if it were going to turn up, it would turn up in spring.

In the middle of a picnic.

You can almost hear Brigham Young’s irrefutable decree, “Any man fool enough to fish a frozen lake will rest within its chilly depths til Resurrection morn.” And leave it at that.

Another man, who didn’t know the first man, went out on his boat to look for the body, fell in, and drowned. Yet a third man who didn’t know either of them went out and suffered the same fate.

By this time, the State had no place to hide. No doubt the Church got the Governor on the phone and said, “Get those brethren out of the lake.”

They sent out the divers and dragged the lake and found all three bodies, and made most emphatic declarations.

UTAH LAKE IS CLOSED.

So there. The old Utah MAR-MONS are of Scandinavian descent, and still haunted — or favored — by these water sprites.

Let’s imagine an audience member from the time of Wagner, sitting down to hear the Ring for the first time. Let’s say they are from one of the old villages where people lived for hundreds of years in the same twenty square miles as their ancestors since the Migration Period, or earlier. They know about the legends of dangerous beauties in bodies of water, and how many have lost their lives in such places.

So they sit down to the first opera, Das Rheingold, and as soon as those Rhine ladies show up, they say to themselves, “This is going to get skeevy.”

It may even be that some abandoned their seats at the first sounds of the sopranos.

You never know about old curses — or the theatre.

You may be taken forever by the Rhine.